Missing the Link? An Argument for Algebra

An article a while back in the New York Times asked the question “Is Algebra Necessary?” It suggested that while math is integral to civilization, we nevertheless should not force it on our students. The argument was that solving an algebraic expression does not necessarily lead to "more credible political opinions or social analysis." This however, is missing a crucial point. Learning math is useful – if not vital - to learning in general. Math and critical reading work together for a synergistic effect of increased learning ability. Most notably, students’ skill levels for math and reading are generally within similar ranges.

To test this hypothesis, I compiled a small random dataset of 56 students, comprised of high school juniors and seniors enrolled in an SAT tutoring program (30 boys and 26 girls). Each student had taken a diagnostic SAT sample test (timed and monitored) from the College Board’s Official SAT Study Guide. This group was a fairly representative snapshot of students interested in improving their chances of getting accepted into college. (While not necessarily representative of all high school students.) In this particular sample, the critical reading and math scores (range 200 – 800 for each) summarized as follows:

Section Avg Score Std Dev Min Max 95% MoE N

Reading 484.64 92.3 340 750 +/- 24.7 56

Math 492.86 89.9 320 700 +/- 24.1 56

Total 970.5 170.6 690 1450 +/- 45.7 56

This comparison is simply looking at a student’s initial reading and math skills and their relation to each other. According to the National Education Center for Education Statistics, the national average math SAT score for about 1.5 million test-takers in 2011 was approximately 514, and for critical reading it was 497. Both national averages are higher than my small dataset of first-timers seeking help, as one might expect. While the average scores of reading and math are relatively close, it does not guarantee that they are generally close for each student.

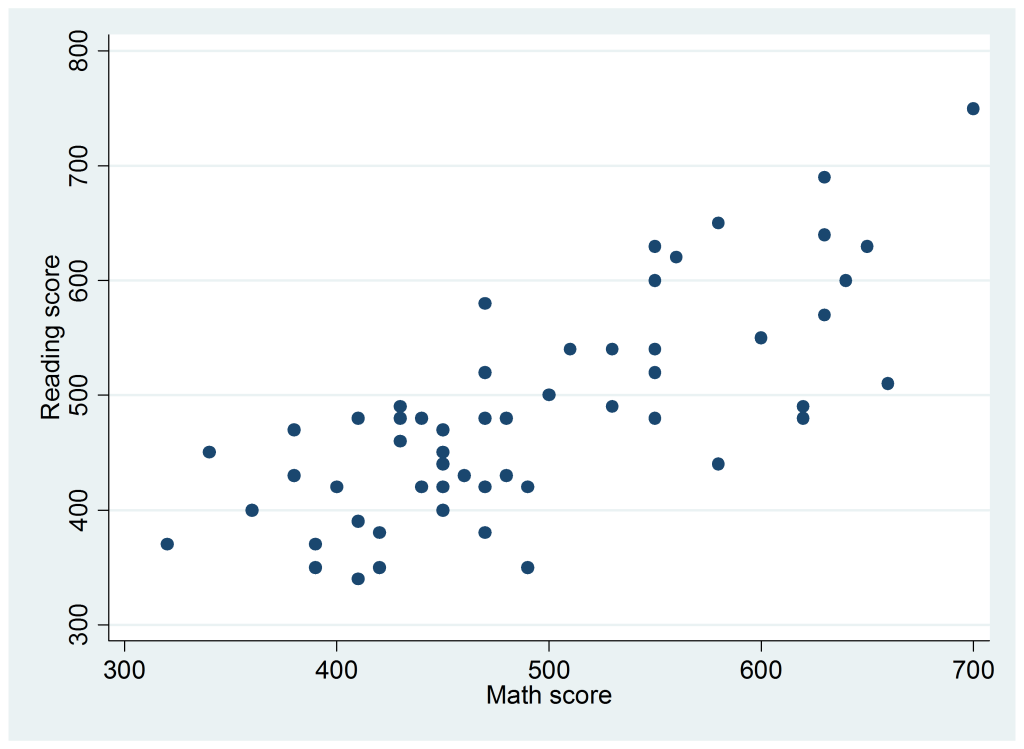

The scatterplot of the associated reading and math scores for the 56 students does suggest a relationship:

As for the difference between each student’s reading and math score, the numbers summarize as follows:

Description # of cases Average difference

Reading score exceeds math score 24 50.8 points

Math score exceeds reading score 28 60 points

Math score equals reading score 4

Average difference btw the means 8.21 points

With this data we can test our null hypothesis (Ho) that the means of the reading and math scores are equal, i.e. that there is no significant difference between them. The alternate hypothesis (Ha) is that the average math score is significantly greater than the average reading score, at a 5% level of significance. Using a paired t test assumes that the means are dependent, since both scores are from the same student. A calculated t score of 0.957 results in a ρ value of 0.17, which exceeds the 0.05 level of significance for a one-tailed test. Therefore, we are unable to reject the null hypothesis. For comparison, we might assume that the means of reading and math score are independent of each other, since they are testing two (seemingly) separate skills. An unpaired t test results in a calculated t score of 0.477, for an even higher ρ value of 0.317. In either case, we fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude there is no significant difference between a student’s math and reading score in general. In addition, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the students’ math and reading scores is a rather strong +0.752.

Confirming my initial observations, a student low in math is typically low in reading, and vice versa. In two cases where the students scored considerably higher on their initial math score than their reading score, English was not their original or native language. Since doing this analysis, I have encountered only one student whose reading scores were dramatically higher than her math scores. This comparison does not imply that weakness in math is causing the weakness in reading, or vice versa, only that they are related to each other. None of this explains why either of the student’s scores is low, only that they tend to be linked.

There are a few logical explanations for the general relationship between the two skills. Unfortunately there is genetics: a student with a greater cognitive capacity for learning may absorb more regardless of the subject. And engaged parental guidance early on is a vital factor toward academic progress. (I jokingly tell my students: “The most important decision you’ll ever make, is choosing your parents.”) Also, a student with the desire to excel in school will likely do well in most, if not all, subjects. Maturity level, the ability to focus, and peer pressure can all contribute to higher or lower performance. A major point is that exercising your brain on one subject should enhance your learning ability in other subjects; it's the exercising that is important. Here is a simple sports analogy: suppose a basketball coach practiced only on shooting (relatively fun and not physically hard), and did not push his players to run wind sprints (physically taxing and not fun). This would be taking away a vital supplement toward maximizing the players’ performance on the court.

The general perception among many students is that they are just not good at math, while remaining convinced they are good at reading and writing. Or, the reason they are not good at math is because they don’t like it, and certainly that is a factor. But the sad truth is that low math ability appears to be in cahoots with lower performance in reading and writing. The numbers do not indicate a tendency for students to be brilliant in one subject while stinking at the other.

As for the original question, one can argue the advantages of letting only those interested in algebra choosing to take it. For one, math scores would likely go up on average. There would be less bored students wasting time they could be spending on, for example, job skills training, networking, website development, self-promotion, social influencing, and reality-show programming. It is likely that there would be the same relatively small percentage of students going to college to be the engineers, economists, doctors, or scientists. Despite how efficient this may sound, my simple analysis suggests how harmful this could be to the collective learning ability of society in general. Harkening back to principles espoused by Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill, a healthy economy and representative democracy depend on an educated citizenry, specifically in the three R’s. As I continuously stress in my math instruction, the focus is improving your problem-solving abilities. And what is the point of “credible political and social analysis” but to solve problems that people are facing?

RKL for MAXimatician.com